My mother and I had a conversation at Mother’s Day dinner about our plane ride when we left Korea to come to the U.S. in 1971.

“Do you have memories of the flight?” my mother asked.

“Not really,” I said. “All I remember is being in a big, empty airplane and playing with a red plastic phone, practicing “Haro, Haro” over and over again.”

“You don’t remember that our plane stopped at Immigration Control in Hawaii? You were seven.” Her eyes probed mine, a look of disbelief, or perhaps disappointment.

I shook my head.

“Well, I remember everything when I was seven,” my mother said. “I remember….”

As I listened intently to her story, memories of my own came tumbling down.

“When I was seven, in 1945, Russian soldiers stormed our house in Pyongyang, waving their machine guns at our faces,” my mother said. “My mother was nursing my baby sister, and I was crouched in the corner trembling with my four siblings. I later learned that the Russians were looking for valuables to take, like watches, but we didn’t have any.”

“When I was seven, you gave me a new name,” I said. “It was ‘Rosa’ from an American baby name book, the letter ‘R’ for Republic of Korea. You gave brother Oliver the letter ‘o,’ and brother Kenneth the letter ‘K.’ You told us not to forget where we came from, but I started to forget anyway.”

“When I was seven, I saw fear in my father’s eyes,” my mother said. “When he came home from work and found out about the Russian intruders, his face turned white, and his lips stood in a straight line. His eyes darted about, as if to make sure no one else was still in the house. He barked at us to pack our belongings, that we would leave first thing in the morning. We went to bed, but none of us slept.”

“When I was seven, I couldn’t speak English. I walked into my second-grade classroom and all eyes turned toward me. Children whose hair color, eye shapes and skin tones were so foreign, whispered to each other in a language I didn’t understand. Everyone was wearing shoes, and memories of my white socks touching the cool floor of my first-grade classroom in Seoul flooded back with longing.”

“When I was seven, I fled the Communists,” my mother said. “I held my little sister’s hand tight and slipped out the front door unseen. We fled Pyongyang under cover of the early morning fog. Father led the way toward the sea, where he said we were escaping by boat. He said the Communist were here, and we had to go south before it was too late.”

“When I was seven, I learned I was different. I was “Chink” and “Jap,” and my eyes were slits. I knew this by the way the kids pulled the outsides of their eyes apart when they saw me. They tugged at my braids and cut my brother’s face. I didn’t know how to fight back so I ran all the way home.”

“When I was seven, I huddled in a boat in the dead of night,” my mother said. “The boat driver said “Shhh” when my baby sister starting whimpering, and my mother shoved her breast in her baby’s mouth to quiet her. “They’re looking for us, so don’t make a sound,” he hissed through his teeth, my own chattering in the freezing cold. The gentle sucking noises my baby sister made were muffled by shots from somewhere close by.”

After this conversation with my mom, I realized there is healing in talking, being in the moment and reliving our stories by sharing them. I learned something about my mom that night, and I understand her a little better now. I saw her when she was seven, and I saw the woman she is today. I remember the girl I was too, and understand a little better, the woman I am now. My daughter explored my childhood in a poem, and I wrote a poem in response, which you can read here.

May is Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, and I am reminded to be gentle with myself, my mother and others. In light of what’s happening in our country with anti-Asian violence, stories like ours should be amplified so we can find compassion and heal. By listening deeply, we are bound to recognize our shared humanity and live a more generous life. I shared my family’s immigration story on StoryCenter’s blog.

I hope we can all ask a relative, neighbor, or friend, what they were like when they were seven. What about you? What was your life like at seven? Leave a comment below.

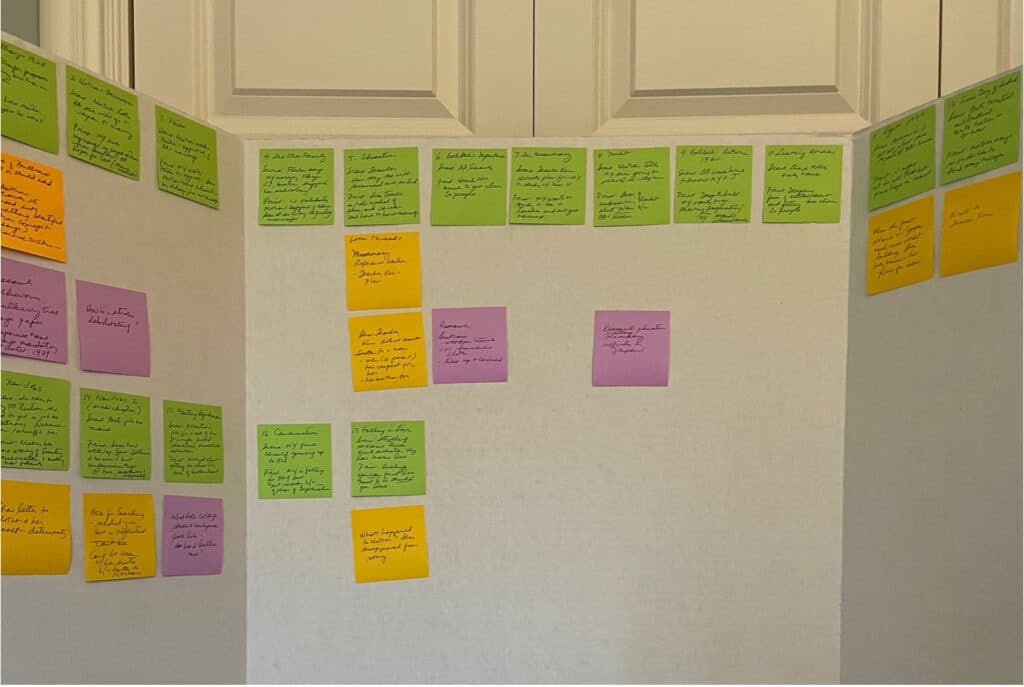

Where I Am in Book Revision

I’m in the process of incorporating comments from three beta-readers. The post-it board here shows my gradual progress (thanks Jennie Nash of Author Accelerator for the manuscript revision tips). There’s still a lot of work to do, but I’ve been motivated by the positive feedback. Readers said, “You have a great story here,” “I looked forward to reading it each day,” and “What interested me the most about White Mulberry were the settings, the historical details (and most of all) the complicated family dynamics.” I sincerely appreciate the time they took to read my manuscript and their encouragement to keep going. The most special feedback was when my father said he cried reading it.

What I’m Watching

In my 20s, I was obsessed with a documentary called Seven Up, examining the lives of 14 British children in seven-year intervals as they mature into adulthood. It tests the maxim “Give me a child until he is seven, and I will give you the man.” It’s fascinating! The Up Series is available at https://www.amazon.com/The-Up-Series/dp/B074MGWDPF. The New York Times also did a feature story on the series titled “Does Who You Are at 7 Determine Who You Are at 63?”

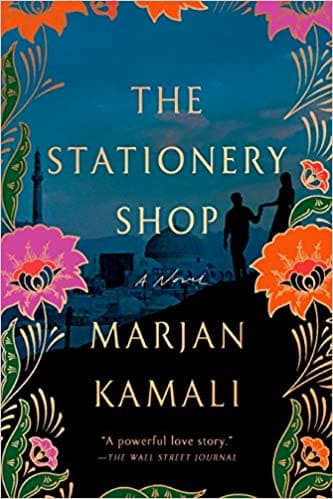

What I’m Reading

A beautiful, poignant story about enduring love spanning the political upheavals of 1950s Tehran to today. It was intimate and heartbreaking. I love historical fiction and I highly recommend this one. Support local bookstores and buy it online at bookshop.org here.

Picture of the Day

Joey and his siblings on their first birthday

Thank you for telling this beautiful story and allowing us a glimpse into your mother’s life in Korea when she was seven and your life in the US at the same age. Powerful stories like this one are necessary as we fight against hatred and teach our country to battle prejudice due to race, religion, sexual orientation, gender, disabilities, etc. I want to know more….can you write “when I was eight” next?

Thanks for recognizing the need to share stories in order to battle prejudice. It’s a mission that’s very important to me. I got a kick out of your idea to do another story about being eight! I’m actually watching the documentary Seven Up now, which tracks the lives of 14 British children over seven year intervals. Maybe I’ll write about when I was 14….

I think it’s beautiful that your mother share her memories with you and that you can have conversations with each other. As my mother is battling dementia, we no longer have those in depth conversations. However, i’m learning to navigate creatively so we can still have those special moments together when she is sometimes lucid. I love your stories as I can relate and reflect on my past as well. Thank you for sharing…

I’m so sorry about your mom. It’s wonderful that you can spend some quality time with her when she is lucid. I can imagine how hard it must be for you to see her like this. I’m sure she feels your love and support. Thanks for sharing.