Happy Year of the Tiger! I had the opportunity to talk to author Juhea Kim about her debut novel Beasts of a Little Land at my book club last week on Zoom. Named a Best Book of 2021 by Harper’s Bazaar, Real Simple, Ms. and Portland Monthly, Beasts is an epic story of love, war and redemption set against the backdrop of the Korean independence movement. We had a lively, engaging and emotional conversation, with laughter and even a few tears. My book club loved the novel and was impressed by the insight, poise and humility of the author.

Here is my Q & A with Juhea. I highlighted those sections I especially admired.

Below is also a little update about my writing progress and an interview I will be doing with author Lisa See in April.

Our Virtual Discussion

Q & A with Juhea Kim

Why did you choose the title and what does it mean to you? Was it intended to be published in the Year of the Tiger or was it just a coincidence?

All my gratitude goes to my brilliant agent Jody Kahn (of Brandt & Hochman), who came up with the title inspired by a passage in the book. The title captures the intensity of the struggle in the Korean peninsula, as well as the mythic/folkloric quality of this work and of course, the centrality of nature in Korean culture. It was published in December 2021 in the US and is being published around the world in the Year of the Tiger (2022), completely due to coincidence. It does feel like a stroke of luck.

There are both western and Korean names in the book, like Jade and MyungBo. You also use the word “courtesan” instead of “giseng.” Why did you make those choices? Were you writing primarily for a Western audience, Korean or both?

I actually don’t think of names like Jade or Lotus as Western at all—just as I wrote Beasts in English but don’t think of the book as “Western.” These names are approximations of pure Korean names (soonwoori mal) that the lower classes would have had. Some readers have commented that giving these names to courtesans is anti-feminist, but you’ll notice that poor male characters Loach and Stoney were also given naturalistic, pure Korean names, the meanings of which should be immediately apparent. In fact, JungHo, who also comes from an illiterate background, notes proudly that his father lovingly bought his hanja (Chinese character) name from a local astrologer. This detail was inspired by my grandfather getting my older sister’s name made—she was his first grandchild.

As for the audience, I had to write a book that makes sense to Western readers to be publishable here. But on an emotional level, I was highly conscious of meeting the standards of Korean readers, because they know the history, the culture, and the spirit that this book intends to portray. While I appreciate hearing from readers of all backgrounds, it feels so special to hear from Korean and Korean-American readers that this book resonates with them profoundly.

This story is told in multiple points of view. Did you originally start that way or did it change? Which character do you relate to the most?

I absolutely, always knew this was going to be told in multiple, close third-person omniscient POV! This is a classic, old-fashioned way of storytelling, of course reminiscent of the Russian greats and my personal favorite, Anna Karenina. But it also has deep roots in Korean epic novels depicting this time period, like Cho Jung-rae’s Arirang, which I read as a child. People often assume that Jade is the character who most resembles me, but she is actually the character who is perhaps the least like me. I am most similar to MyungBo, the idealist—and of course, the ferocious tiger.

The first scene in your book is a prologue about the hunter and the last scene an epilogue about the sea women in Jejudo. Were those scenes always the beginning and end? Did you outline your book or write as you went?

Perhaps unbelievably, these bookend scenes appeared in my mind from the very beginning. I wrote both of these chapters in one sitting, and both didn’t change much at all through the years, so that what you read in this published book is pretty much what I drafted. The middle of the book, however, underwent many changes despite the general story arc not changing much.

Why did you decide to write this book and why does the world need it now?

I became a writer because of an inevitable, irresistible need. Writing is a hard vocation—you open yourself to a myriad of vulnerabilities and failures, and even when the work is going well, you feel under extreme physical and mental torture. But I still wanted to write seriously, and my agent told me that I needed to write a novel in order to be published. So, I chose the most personal and authentic story I could tell… No slim and literary 270 pp debut novel this, but an epic saga that at one point weighed in at 120,000 words. (I really, really wish I could write a literary novel where nothing happens except inside the protagonist’s head. I do like that sort of book especially if I’m in the mood. But it’s outside my powers.)

Looking back, I am just aghast at my naivete—but even that is what makes the book what it is. Beasts is a very earnest book written by a very earnest person. It discusses themes like love, friendship, ideals, duty, courage, and redemption without any irony—it takes all those things very seriously. It believes in the power of literature to awaken our humanity and to console our grief. I think that’s why it has received such wonderful feedback from readers around the world: because people, especially outside of the US, lead more difficult lives, and they need books that can save them.

How has your background in art history and music informed your writing?

As a writer, I’m much more often inspired by music than by other books. There are certain pieces of music that haunt me for years, and the effect that they have on me is what makes me think, “I wish I could do this, but through writing.” This isn’t to say I don’t read books that make me envious as a writer, but the books that most thoroughly impress me also frequently strike me as impossible and unwise to emulate. I worship Bulgakov but I could never write like him, for example.

My longer works always have a musical archetype, and when I get stuck somewhere in the middle of writing, I listen to the source code. That helps me understand solutions to the writing problems. And then my art history training gave me the foundations of writing. That discipline taught me how to describe what I see in the most precise way. The elegance here comes from clarity rather than cleverness. There are many ways to write beautifully, but the art historical way of writing feels most intuitive to me.

What was your research process like? Since you read both Korean and English, did you use Korean primary sources and how were they helpful? Do you speak any other languages and how has your interest in world languages influenced your writing?

All the research I did for this book was in Korean: history books, articles, fiction from early 20th century Korean and Japanese writers. I had been reading these books organically since I was little, and when I started to write this novel in earnest, my dad shipped some of them to New York for me.

In addition to Korean and English, I also speak French. I absolutely think that all these languages influence my writing, although I only write in English. In my head I switch between these languages, even French depending on the context, because certain situations just make more sense in a certain language. This is because language shapes our thoughts and values. Although written in English, Beasts is heavily informed by Korean, which is a highly idealistic, relational, warm, affectionate, even passionate language. And all those qualities describe the book, too.

What happened before and after the book deal? What was the relationship like with your agent and publisher, and how have they supported you since the book has come out?

When I got the book deal in September 2020, I honestly thought I had no further desire in this lifetime; my deepest wish had been fulfilled already, and everything else was going to be a bonus. Well that’s certainly not what happened! I continued to form new wishes—I wanted the book to succeed, win praises from critics and readers, and cultivate my long-term career as an artist. It’s a lot to process, and my agent has been my most steadfast champion throughout this debut author journey.

What has been your greatest surprise in writing this book? What did you expect that didn’t happen, and what happened that you least expected?

Everything feels like a surprise, honestly. I didn’t expect the book to be a “Big Book,” as they say in the publishing industry. I knew that it was being spotlighted months leading up to publication, but my expectations for its commercial success were lower. I also didn’t expect how passionately readers would respond to this book, and how much I would care. I save every lovely Instagram post and message and email that I get from readers and respond to each one. I feel so humbled by their support and wish I could offer them a big jeol (a big Korean formal bow, essentially). I dedicated my first book to my parents, but from now on everything I write will be for the readers. I also didn’t expect we would sell foreign rights the way we did. There is a saying in Korean, “The most Korean is the most universal.” It means that the most authentic thing is also the most widely appealing, and I’m shocked that this deeply Korean story, something that I was afraid would never find traction in US publishing, is leaping around the world in countries as far apart as Brazil, Saudi Arabia, and Russia.

But to be honest, not everything about publishing my novel has been a joyous surprise. I was also shocked by the anti-Asian racism I faced. After one review in a nationally ranking newspaper, I actually wrote a letter to the editor, and while they didn’t change the racist passages, they ended up posting a huge corrections section listing the dozen or so factual errors. In that review, for example, the white critic claimed that my book is “teeming with gaming parlors.” I didn’t even know where she got that from (my book has none), until a fan pointed out that the critic was confusing my book with Pachinko.

My experience also seems to reflect the rise of anti-Asian hate crimes and the fear of the success of Korean culture worldwide (hallyu). Finding community has been so important to protecting my mental health. And the more I discussed these issues with my fellow Asian authors, the more I realized it’s a systemic issue.

What are you working on next and why did you choose this project?

I’m writing a novel about ballet, one of my lifelong passions. Whether it’s a small project or a big one, I only try to write things on which I can stake my whole soul. I have to believe in it with every part of my being. If it’s anything less, the struggle isn’t worth it.

Beasts of a Little Land is available at your local library and for sale everywhere. Please follow Juhea at www.juheakim.com and on Instagram and Facebook @juhea_writes.

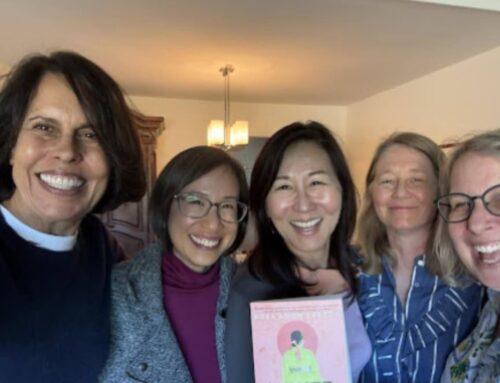

Our Book Club

A Little Update on My Writing

I am smack in the middle of a Pub Crawl publishing intensive through StoryStudio Chicago and gearing up to pitch my novel, White Mulberry, to agents and editors. It is nerve-wracking, exciting and humbling. It’s been great to meet new friends and learn about the publishing world. It was particularly nice to get words of encouragement from Juhea about my work.

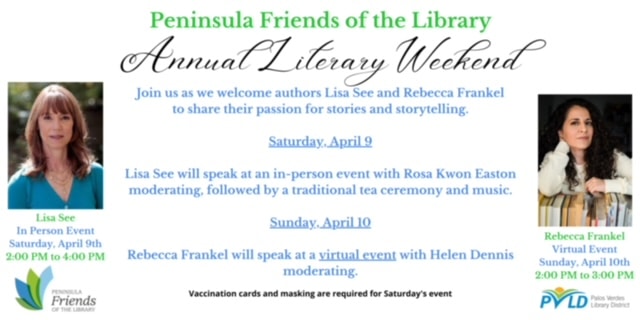

On Saturday, April 9th, I will be interviewing author Lisa See in person at the Malaga Cove Library as part of the Peninsula Friends of the Library Literary Weekend. It will be followed by a traditional tea ceremony and music. I will post more about this exciting event in the coming months. Let me know if you have any questions you want me to ask Lisa!

Thank you for your ongoing support of books, authors and writing. Please comment on the Q & A, if you have any book recommendations, or you just want to say hi!

What I’m Reading

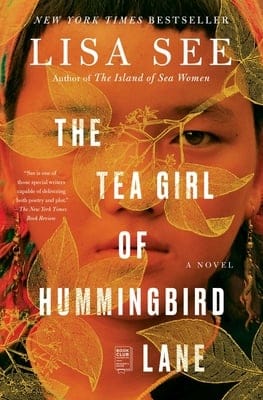

The Tea Girl of Hummingbird Lane

A powerful story about circumstances, culture, and distance, The Tea Girl of Hummingbird Lane paints an unforgettable portrait of a little known region and its people and celebrates the bond of family. bookshop.org.

Photo of the day

My book club knows how to lay out a delicious spread, and celebrate members’ birthdays! Happy Birthday Susan!

Leave A Comment